With all of the sites on Middle-earth Network we get to view all of this great content in one place, but sometimes certain gems get lost in all of the posts. From time to time we’ll be featuring posts from others that deserve some special attention. This week our featured post is from Dwim’s Depository. You can view more of her thought provoking posts here.

Wisdom, according to Aristotle, falls into two categories: practical and theoretical, known in Greek as phronesis and sophia respectively. Both current events and literature serve as examples of the practical and theoretical wisdoms along with the morality that affects them. A formation of a breakfast club serving as neutral ground for Democrats and Republicans to discuss legislation is the prime example of phronesis and sophia combined, while J.R.R Tolkien’s wise wizards, one good and one evil, serve as example of the wisdoms as separate entities. Furthermore, Robert Coles’ essay discusses the clash between moral knowledge (sophia) and moral action (phronesis), which is exemplified in Tolkien as well as the hope that the two can coexist, an occurrence proven by the existence of the bipartisan breakfast club.

In the classic work Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle discusses phronesis and sophia, two types of wisdom that the ideal man must have. Phronesis, or practical wisdom, is defined as “the capacity of deliberating well about what is good and advantageous for oneself” while sophia, or theoretical wisdom, is “[a] most precise and perfect form of knowledge” that encompasses scientific knowledge and abstract concepts that are dealt with in philosophy (Aristotle 152, 156). Aristotle provides the example of theoretical wisdom in the form of a wise man who “must not only know what follows from fundamental principles, but he must also have true knowledge of the fundamental principles themselves” (156). Practical wisdom is seen as wisdom governing the actions of man, while theoretical wisdom governs intangible concepts. Morality plays a part in both types of wisdom, as a moral man must have knowledge of what is good along with the intentions to perform good.

In a recent article titled “Simple Menu for Bipartisan Breakfast Club”, Jennifer Steinhauer reports on the foundation of a breakfast club started by two freshman of the House of Representatives who “simply long to get something, anything, accomplished without the rancor, posturing and divisieness that has characterized most of the last year in Washington” (Steinhauer). Representative James B. Renacci, a Republican from Ohio, and Representative John Carney, a Democrat from Delaware both exemplify Aristotle’s definitions of phronesis and sophia, taking action with their well-meaning intentions though the formation of the breakfast club where “the group meets to talk about legislation they can agree on” despite the fact that “this year has been more difficult than most, considering the deep differences between the two parties” (Steinhauer). Starting off with two men, the “next meeting started with a few more and then there were a few more and now [amounts to] about 12” (Steinhauer).

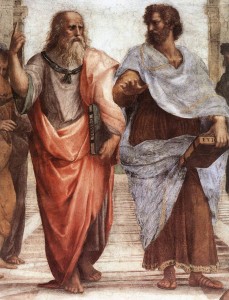

J.R.R Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy features a council of five wizards, two of which are Saruman the White and Gandalf the Grey. Where Steinhauer’s article reports on men who represent both phronesis and sophia together, Tolkien utilizes phronesis and sophia separately in the forms of Saruman and Gandalf respectively. Tolkien’s usage of both types of wisdoms not only highlights the need for both to be in accordance, but also the moral ambiguity within phronesis. Saruman, through the use of cleverness, an aspect of phronesis, becomes a secondary antagonist in order to take advantage of a situation to better his station in life. Gandalf is the opposite, choosing to abide by a moral code and the idea of righteousness, thus identifying him as an example of sophia.

Aristotle delves deeply into the meaning of phronesis, focusing on its ability to lead to good or bad results by addressing the moral alignment of practical wisdom, which differs from cleverness. “If the goal is noble, cleverness deserves praise; if the goal is base, cleverness is knavery. . .[but] this capacity alone is not practical wisdom, although practical wisdom does not exist without it (emphasis added)” (Aristotle 170). Thus, practical wisdom as a whole is seen as a morally good concept, “for wickness distorts and causes us to be completely mistaken about the fundamental principles of action. . .a man cannot have practical wisdom unless he is good” (Aristotle 170). However, within the whole of phronesis lies cleverness, which can be utilized for both good and bad purposes.

Phronesis as a whole is best exemplified by the actions of the Representatives who founded the breakfast club, which features “a few bylaws, to prevent the outbreaks of partisanship. . .[and the tendency to] reflexively denounce another member’s ideas” (Steinhauer). Though the founders are both freshman within the House of Representatives, the club also includes those who have worked in other legislatures that used bipartisanship as a survival technique (Steinhauer). The group has not only come together to further a common good, but has sponsored a bill that would “give incentives to employers to hire long-term jobless people along with the Creating Homeownership Opportunity Act, which would establish pretax savings accounts that can be used for the down payment on a first home” (Steinhauer).

The cleverness found within phronesis is best exemplified by Saruman, Tolkien’s corrupt wizard who seeks to persuade Gandalf the Grey to join him on the side of Sauron, the Dark Lord, as well as using the One Ring of Power, attempting to justify it for the greater good. “. . .[We] must have power, power to order all things as we will, for that good which only the Wise can see. . .There need not be, there would not be, any real change in our designs, only in our means” (259). With subtle deception, Saruman’s cleverness is used for a base goal, thus differentiating himself from the virtuous phronesis with his skewed perception of what is good, as well as his failure to percieve the danger of using the One Ring.

In contrast to the moral ambiguity within phronesis, sophia can be seen as a morally good concept that solely deals with the knowledge of morality and other abstract ideas. In contrast to the reaction of Saruman to the notion of power, Gandalf, when faced with the One Ring, exclaims “Do not tempt me! For I do not wish to become like the Dark Lord himself. Yet the way of the Ring to my heart is pity, pity for weakness and the desire of strength to do good” (61). Gandalf, through his knowledge of power and the Good, refuses to use the Ring- despite his good intentions- for fear of being corrupted by the power within the One Ring that would utilize its wearer for its own purposes. Just as Aristotle’s wise man not only understands the consequences from following an idea but also the idea itself and what it means to mankind, Gandalf is the exemplar of Aristotle’s theoretical wisdom.

Ultimately, phronesis and sophia should be in accordance to achieve the most good for all. Both Steinhauer and Tolkien’s works feature men who exemplify the combination of intent and action where “a man fulfills his proper function. . .[where] virtue makes us aim at the right target, and practical wisdom makes us use the right means” (Aristotle 172). This coexistence reflects an ultimate good where knowledge of what is good (sophia) leads to a good action (phronesis). Aristotle realized that the ideal was simply a standard which no one could attain, but by striving towards such an ideal, man would gradually become good through theoretical and practical wisdom.

Coles’ essay titled ‘The Disparity Between Intellect and Character’ asks “’What’s the point of knowing good, if you don’t keep trying to become a good person?’” (2). The disparity between knowing good and doing good is highlighted through the struggles of a young college student who “encountered classmates who apparently had forgotten the meaning of please, of thank you—no matter how high their Scholastic Assessment Test scores” and the realization that no matter how much a student could learn what is moral, it does not make them a moral person (2). This disparity between knowledge and morality serves to highlight the need for the ideal good where the two are combined, and the student’s experience challenged Coles, a professor at Harvard, to “make an explicit issue of the more than occasional disparity between thinking and doing” while avoiding giving his students a chance to turn a moral challenge into an opportunity where egos could be inflated (2-3). Through his advocacy forh is awareness on the disparity between moral knowlede and moral action through teaching, Coles has found that “many students will respond seriously, in at least small ways if we make clear that we really believe that the link between moral reasoning and action is important to us” (4).

Coles and Aristotle both recognize the need for action and intention to match, and that “moral reasoning and reflection of character can somehow be integrated” (Coles). Coles’ moral reasoning corresponds to phronesis, whereas moral reflection corresponds to sophia, as both concepts deal with theoretical concepts as opposed to concrete actions. Aristotle’s statement that “in intellectual activity concerned with action, the good state is truth in harmony with correct desire (emphasis added)” would ring true for Coles, as he saw glimpses of the good life within his students’ work (Aristotle 148). For example, a student had thanked a cafeteria worker, which then led to a conversation between the two. For that student “she had felt that she had learned something about another life [and] had tried to show respect for that life” (3). For Coles, “best of [the students’ work] were small victories, brief epiphanies that might otherwise have been overlooked, but had great significance for the students in questions” (3).

Coles would view the formation of the breakfast club as an example of moral reasoning and moral reflection coming together to create good, as the reflections on the House of Representatives and its divisiveness led Representatives Renacci and Carney to act morally by forming the breakfast club as a neutral or even cooperative ground for members of either party to discuss legislation and potential action, taking “that big step from thought to action, from moral analysis to fulfilled moral commitments” (Coles 3). Representatives Renacci and Carney, by recognizing a need for a meeting ground through the analysis of the current tension between parties, took action and fulfilled moral commitments. The breakfast club, “without the attendant news conferences and self-celebrating news releases”, acts as the opposite to some of Coles’ students that seek to glorify their own achievements instead of focusing on the ability to do something good because it is good as opposed to taking action for the wrong reasons such as personal glory (Steinhauer).

With Tolkien’s wizards as exemplars of practical wisdom and theoretical wisdom, Coles’ realization of the idea that “the study of philosophy—even moral philosophy or moral reasoning– doesn’t necessarily prompt. . . a determination to act in accordance with moral principles” is solidified (2). Despite the knowledge and wisdom that Gandalf and Saruman possessed, the two were on different paths when it came to perceiving what was good in drastically different ways, with Saruman opting for power over peace and Gandalf fighting against the corrupting force that is power. Despite Saruman’s appeal to theoretical wisdom in using the One Ring, Gandalf retorts “I would not give it, nay, I would not even give news of it to you, now that I learn your mind” (Tolkien 260). With the discovery of Saruman’s ill intentions and a terrifying idea of what the consequences would be if the One Ring were to be handed over, Gandalf’s theoretical wisdom and adherence to the Good is emphasized through his refusal.

With practical wisdom and theoretical wisdom as guiding concepts to the good life and the makings of an ideal man, Aristotle, Tolkien, Representatives Renacci and Carney as well as Robert Coles would agree that while morality and knowledge are two different concepts that may be able to stand alone and promote good within their respective spheres through either reflection on what is good or taking action by doing what is good, they are best when combined, creating a path to the good life paved with good intentions.

Works cited

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1999. Print.

Coles, Robert. “The Disparity Between Intellect and Character”. Chronicle of Higher Education.

September 1994. Print.

Steinhauer, Jennifer. “Simple Menu for Bipartisan Breakfast Club.” New York Times. 18 Nov 2011:

A19. Print.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005. Print.

About Dwim

Call me Dwim for short. I am a loyal subject of the kingdom of Rohan and a budding scholar. Find me on the Riddermark server on LOTRO if you’d like. Fancy a chat or have a question? Leave a comment or send me a message on MEnet! (Interesting comments or conversations may end up here on my blog!)

2 Comments