On March 25th is the long awaited Tolkien Reading Day so all month long in March, we, along with some of our readers, are reading Tolkien’s Beren and Luthien over in our Facebook group. If you’re curious to join, there is still time so why not head over to our Facebook group?

Disclaimer: This post contains spoiler.

As many other readers, I’ve encountered the tale of Beren and Luthien in The Silmarillion. Since I haven’t read any of the History of Middle-earth books, much of what I discovered in Beren and Luthien was new to me.

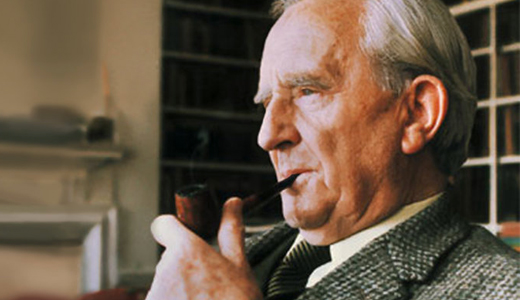

As a hobby writer and artist, I love watching or learning about a writer’s or an artist’s progress. Seeing how a text or painting changed over time, is as much interesting to me as admiring the finished project. In Beren and Luthien, we are given a detailed chronology of how Tolkien’s greatest love story changed over time. J.R.R. Tolkien is know for his perfectionism and his constant re-writing of his mythology so I’m extremely exited to finally get a glimpse into his writing process.

In the earliest version that survived, many elements of the tale, people, and names are already somewhat familiar. It is, however, somewhat unusual to read „Gnomes“ as an early term for the Noldor. As Christopher Tolkien points out, his father J.R.R. used „another word Gnome, wholly distinct in origin and meaning from those Gnomes who nowadays are small figures specially associated with gardens“ (Beren and Luthien p.32):

„This other Gnome was derived from a Greek word gnōmē ‘thought, intelligence’ (Beren and Luthien p. 32.)

Despite knowing that, I struggle to banish those tiny garden creatures out of my head whenever reading ‘Gnome’ in Beren and Luthien.

One of the more striking differeces between what we know of in The Silmarillion and its earlier version titled “The Tale of Tinuviel” is how unpolished it feels. Again, many elements of the plot and characters are already there, but this early version seems to lack the depth of what we know of Beren and Luthien in The Silmarillion. In “The Tale of Tinuviel”, the love between Beren and Luthien seems almost shallow. While reading this tale I couldn’t help but think of a Romeo and Juliet type of romance where both lovers barely know each other, but are willing to risk it all nonetheless. As one of our readers named Marius G. commented in our Facebook group, the love between Beren and Luthien feels very shallow: „Especially Luthien’s feelings seemed more like she loved Beren’s admiration of her dancing instead of Beren himself. “ In later versions, such as the various extracts from “The Quenta”, this shallow love changes into the deep love we know from The Silmarillion.

In terms of writing style, I was truly surprised to find that J.R.R. Tolkien made use of ‘a tale within a tale’ in “The Tale of Tiniviel”. As we come to the end of that tale, it is revealed that someone told the events to someone else. This stylistic choice tries to give a sense of ‘history long gone’, but I think that Tolkien succeeded to give this feeling of ‘history long gone’ in his later writings more than in his attempt of ‘tale within a tale’.

Another thing that stood out to me was his usage of words such as god, hell, and rape in his early versions of the tale. While “The Lay of Leithian” resembles a lot of the version in The Silmarillion, the words god and rape stand out profoundly. In his later works, no matter how vile Morgoth, Sauron or the orcs are, the word rape, or allusions to it don’t occur. Yet, in the “Layof Leithian” we encounter a very striking passage:

Nereb looks fierce, his frown is grim.

Little Luthien! What troubles him?

Why laughs he not to think of his lord

crushing a maiden in his hord,

that foul should be what once was clean,

that dark should be where light has been? (Beren and Luthien; “Lay of Leithian” p. 128 line 452-457).

Nereb is, of course, Beren disguised as an Orc. I’m very curious to know what made Tolkien decide to remove the word rape and all direct allusions to it in is later works. Considering the death and slaughter that occurs in The Lord of the Rings, I cannot imagine that ‘being child-friendly’ was a reason to omit ‘rape’.

The later omission of words such as God, heaven and hell make sense to me. These words are rooted in our world and belief systems and feel out of place in Middle-earth.

Source: spiegel.de

Speaking of Nereb, there were a few passages that made me laugh out loud. In “The Lay of Leithian” Felagund, Beren, and company stumble one day upon a heard of Orcs. They slay the orcs and Felagund uses all kinds of tricks, including magic, to discuise himself and his company as orcs. Their disguise is so succsessfull that other orcs don’t recognize them. Only Thû, or Sauron, is suspicious. So when they are brought in front of Thû, they are asked for their names and they simply introduce themselves as Nereb and Dungalef. I don’t know why but this entire passage made me lough out loud. They put so much effort into disquising their physical appearance, but cannot think of better names than their real names spelled backwards, or almost as in the case of Felagund.

There was also a passage in „The Tale of Tinuviel“ that had me laugh for days. In this early version, the reader encounters the mighty and evil cat lord Tevildo. We are introduced to several of Tevildo’s cat servants including his cook Miaulë. I don’t know why but Tolkien giving an evil cat the name of Miaulë makes me laugh. He put so much efford in deriving words from acient Greek, giving characters more than one name filled with meaning upon meaning, and then there is Miaulë. The fact that this name is so close to Aulë makes it even better. I may not have a favourite quote to share with you, but Miaulë is entertaining compensation, don’t you think?

What about your reading progress? Have you read, or are you currently reading, Beren and Luthien? What are your thoughts on it? Leave us a comment down below and join our Facebook group!